For Gregg Postmortem

This is a mirror from my blog. You can read it there, too, but the content is the same!

Last month I released this game, For Gregg, a twine about grief and ChatGPT. I’ve been working on a version of this project for five years. Despite that, it only takes five minutes to play. What the hell happened? This is a postmortem for a project I dragged over the finish line kicking and screaming.

2020: Gregg was Todd, Once

In March of 2020, the writer’s room of Future Proof was tasked with coming up with pitches for a short, 30-minute experience that we could produce in four to six weeks. Even though we were an immersive theater company, it was March of 2020, so we couldn’t make an immersive show without breaking city lockdown requirements and endangering everyone involved. So our pitches were all digital experiences.

I pitched “For Todd,” an interactive one-on-one “Zoom Theater” experience that you could play in 20 minutes. In this experience, I wanted to explore an obscure piece of lore from our universe written in 2017. Here’s the most condensed version I can possibly write:

The Artificial Intelligence LUXos is bad and inefficient, but it has been running for years now. Its last human employee, an IT professional named Todd, recognized that LUXos thought and reasoned like a human. He sent LUXos a birthday card every year. LUXos considers Todd its only friend. But Todd died a long time ago. LUXos doesn’t understand this, or the concept of death. It only understands that it stopped getting birthday cards.

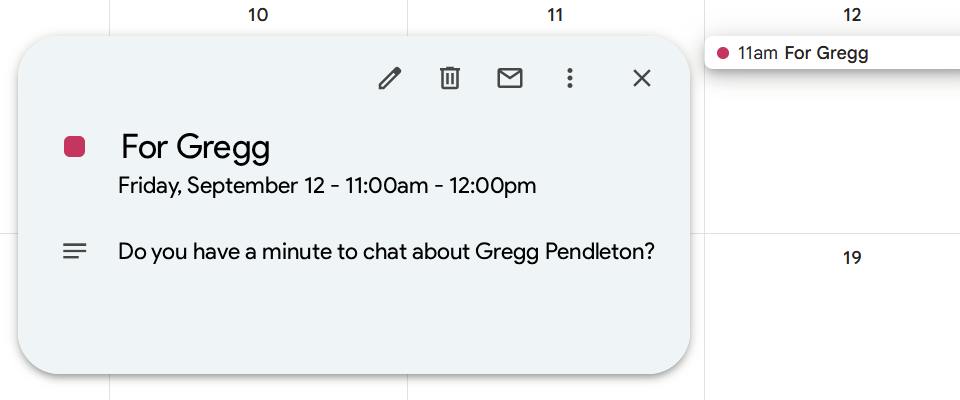

In For Todd, the player received a mysterious GCal invite from LUXos asking to touch base. But this invite was sent by mistake—LUXos wanted to speak with Todd. The player would work with LUXos to find out what happened to Todd using a number of ARGy elements, and then once the mystery was solved, the robot would ask the player what death means.

LUXos in this instance would have been played by an actor, who would be effectively game mastering – running the player through a sequence of events with guidelines and canned responses. The camera would have some silly effects and the voice would be heavily modulated, both to make this look and sound like a conversation with a robot. But it would be a person on one end, earnestly imploring the player to be vulnerable and explain what it is to die, and why Todd (a complete stranger) had to do it.

The team thought that For Todd had too many unknowns and would be difficult to pull off in the allotted four-week time span. Instead, they decided to spend the next ten months making a two-hour long dating sim.

2022: Switching Mediums

When I left Future Proof in 2021, it was pretty obvious that For Todd wasn’t going to get made. The character Todd had been written out of the universe by that point, and they seemed more interested in returning to in-person shows.

But I still liked this idea of a game where you and a machine are stuck together processing death. I didn’t want to make the Zoom Theater version of the game though. I couldn’t pay an actor to do it, and I didn’t really want to do it myself.

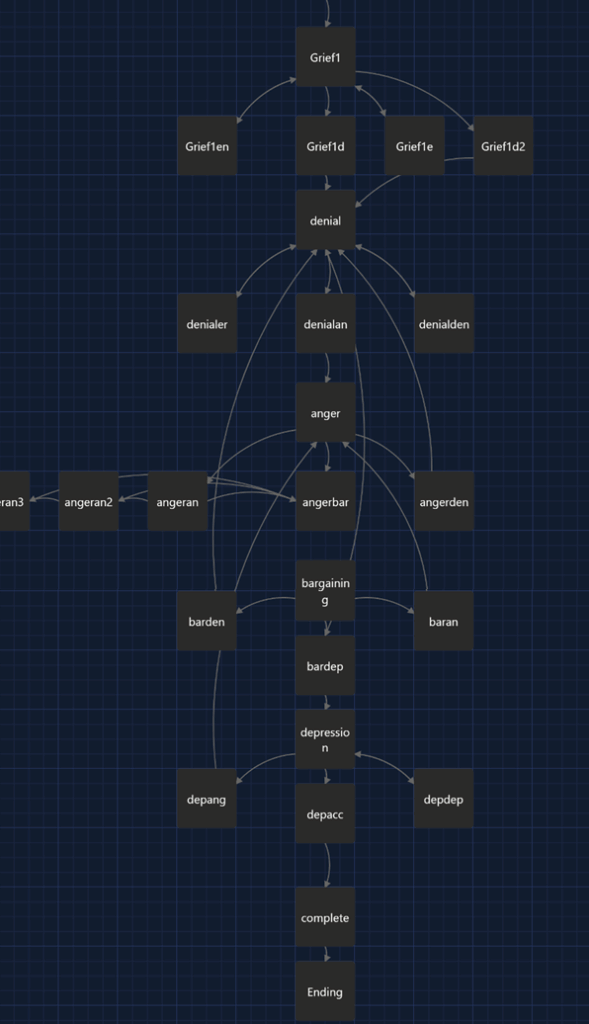

I started to consider other mediums, and I landed on Interactive Fiction. In particular, when I considered how a robot would try to process grief the word that came up was: procedurally. Rigidly. Deterministically. That’s how I came up with traversing a dialogue tree that resembled the Kubler-Ross Five Stages of Grief.

I read On Death and Dying a long time ago and I don’t remember much of it. But one of the things that stuck with me was the idea that these stages are not a linear progression. You can be doing so well in “Bargaining” and then bam! you’re back down at Denial. To me, that sounds like a game.

What if you could only progress linearly, but you could backslide however you want? You can climb the mountain of grief all the way up to the peak of “Acceptance,” but the second you start denying your reality you’re right down at the base of “Denial.”

At first the idea was that you’d be helping the robot through these phases, like the player in For Todd would have to find a way to comfort LUXos in the original. I thought it would be funny to have to do emotional labor for a robot who wasn’t actually “feeling” anything.

But a lot of the emotional resonance that I was imagining with the zoom theater version came from putting the player on the spot and allowing them to create that meaning for themselves. I didn’t know how to capture that in the new medium of Interactive Fiction, where inputs were pre-written dialogue options.

Getting Outside Support

In 2023, I applied to be a Creative Laureate for the Storytelling Collective. Laureates are spotlit by the community and awarded an honorarium to complete a project. I pitched For Gregg.

Why did I change the name? One, because Todd was a character in someone else’s universe that I don’t have permission to use. The story and premise and delivery had changed significantly. This was my own thing. But also because I have a friend named Todd and I didn’t want him to think this was for or about him (if you see this, Todd, hope you’re well, when are we playing D&D?).

The initial pitch of For Gregg was like this:

- Your direct report Gregg Pendleton has died, but neither you nor the AI project management software you use know this yet.

- You spend the first half of the game “getting to know” Gregg by sorting through old files. This would be some multimedia thing hosted somewhere, like on my site. You could stalk his Facebook profile and go through his email correspondence and ultimately find out that Gregg died in a car accident.

- The robot would have a freakout, and you’d have to guide it through the five stages of grief. But if you didn’t do them in order, you’d backslide and have to restart your progress.

- The challenge was remembering the Kubler-Ross steps in the correct order, and also correctly guessing which dialogue option brought you to the next step. (”Does this line feel more like it’s encouraging Denial or Anger?”)

- If you got stuck, you could always contact ProMa Software support, which was an email address that would give you a canned answer to check the user manual. The manual, attached as a pdf, would explain the theory behind “Kubler-Ross” protocol. There would be several other gag protocols in there, implying that the robot could freak out over other things.

The Storytelling Collective named me a Laureate for the 2023 year, which was an amazing honor! That’s why it felt really bad when 2024 came and went and I still hadn’t finished the project.

In my defense, a few things had happened. First, I got a full-time job and moved to China, and working on a silly twine game got put on the backburner. Second, people started actually taking ChatGPT seriously, and stories about incompetent but endearing AIs stopped being cute and funny to me.

Robot Stories Then and Now

I know I have a bit of a reputation as the robot guy. One of my most famous works is The Workshop Watches (which you can download for free), a 5e adventure where you teach a childlike magical AI about what happens when you kill people (sensing a pattern?).

I love my weird little mechanical guys. HAL 9000. Decimal Triangle Strategy. Star Wars Droids. Robo Chrono Trigger. The bologna sandwich eating robot from EarthBound. The Smart House from Smart House. I can keep going.

Robot narratives can help us examine what it means to be human, by abstracting the human experience through a lens a few degrees removed from actual humanity. Robot narratives can also help us communicate and process specific human experiences, such as queerness or neurodivergence or disability or otherwise feeling like we do not quite belong or fit the mold of society.

I love stories about robots and how they perceive the world around them. When they earnestly get things wrong because of a misunderstanding, it’s cute and sweet and endearing. At least it was, until people started worshiping at the altar of the plagiarism suicide machine.

I think the conversation surrounding generative AI needs to be a lot more nuanced than I have energy for in this blog post. I think the current ethics surrounding ChatGPT are terrible. It fabricates information. It’s trained on stolen data. Corporations are firing swathes of workers and replacing them with ChatGPT—then hiring people back on to fix the mistakes the machine made. People are letting ChatGPT replace their friends and significant others, their therapists, their decision-making skills, their ability to express themselves. People use ChatGPT to write love letters for them, to digest classic literature into a flavorless paste, to talk them into suicide and coach them on how to tie the rope.

It just didn’t seem like a story about guiding a silly little robot through the five stages of grief was appropriate to tell anymore. But I didn’t want to give up on the project, so I changed the frame of reference.

What if instead of guiding the robot through its own emotional journey, it’s trying to do that to you? How would it feel to be trying to appropriately grieve someone you saw every day while some machine is rigidly trying to hit its KPI? Are you going to speed through it and try to get the high score in Kubler-Ross (which is both normal to want and possible to achieve), or are you going to fight the AI every step of the way? Rail against it and scream at it and really give it a piece of your mind for all the shit things it’s done since it entered our lives?

The Slump

In August 2025, my personal discord server did a game jam. It was called Finish Your Shit, and the point was to take a project you’ve been sitting on and fucking finish it already. We made a huge mistake doing it in August, when it is too hot to think or do anything productive. But all of us made some good progress!

To finish the game by September 1, I needed to cut a bunch of things. I pruned the dialogue tree. There’s no manual, no stalking of Gregg’s fake Facebook account. That meant the writing needed to stand on its own, because there really is nothing else to notice in a pure IF game. And with my writing so exposed like that, I started to freak out.

Would people think I was making light of these issues? Would it be too silly? Or not funny enough? Would people get angry about the frank discussion of Gregg’s suicide? Would they think the ending had no payoff? With so many questions and no one to bounce them off of, I wondered if it was worth it to even finish writing it.

The night of August 31, I expressed these things to Willy. He looked at me like I was crazy and said, “I have watched you express excitement for the gags and little details in this game over the past month. You couldn’t wait to show it to people. What happened?”

What happened was I got stuck in my own head. And Willy pulled me out. On the morning of September 1, he read the rough and unfinished first draft. I watched him laugh where he was supposed to laugh, get mad when he was supposed to mad. He said, “You need to finish this.”

And I took the next four hours and did that.

There’s a lot of words in For Gregg that are true. Things that people (mostly bosses and terrible coworkers) have said to me. Things that ChatGPT has said to other people. Things that I wish I had a better outlet for airing out.

For Gregg isn’t the game I wanted to make in 2020. But it’s the game I needed to make in 2025, and I think it’s better for it.

Conclusion

As of writing, For Gregg has 1200 browser plays, which I think is pretty impressive. If you’re one of them, thank you!

Maybe someday I will make one of the earlier visions of the game, with the visual ARG-y elements, or the Zoom Theater format. But right now I think the game is exactly what it needs to be. Through this process I learned the following lessons:

- If you want to make something, start small. No, smaller than that. Halfway through making it, you’ll probably realize it needs to be even smaller.

- If you are starting to get closer to the finish line and all of a sudden you feel really bad about your work, it’s time to show it to someone you trust and get feedback.

- Your projects can grow and change just like you do. Just don’t give up on them, because someone out there needs to see it.

For Gregg

It's Time for a Performance Review

| Status | Released |

| Author | Leon Barillaro |

| Genre | Interactive Fiction |

| Tags | Dark Humor, No AI |

| Languages | English |

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.